Tags

American History, Columbus, first woman, food, History, Ohio, Ohio History, Ohio Women, Ohio Womens History, Restaurant, Restaurants, Women, Women's History

This article was copied from The Boston Hospitality Review, and the images, as explained below come from the Columbus Metropolitan Library, Columbus, Ohio. I hope you will enjoy reading this as much as I did.

By Jan Whitaker

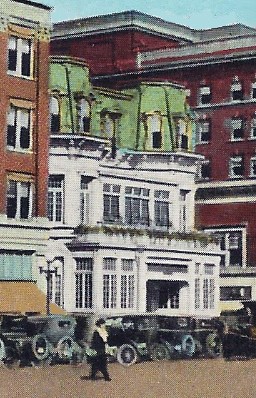

In the summer of 1920 a woman named Mary Love opened The Maramor, a tea room-style restaurant in downtown Columbus, Ohio. The location was in a house once owned by the city’s richest man. After being vacated by his widow in 1895, the handsome 3-story building had housed a variety of tenants including doctors, a Turkish bath, and the State Palace, a Chinese-American restaurant.

The Maramor quickly earned a following. By the mid-1920s it was recognized as one of the country’s fine restaurants, an evaluation based mainly on the quality of its food. Popular dishes included Grape Cheese Salad and Creme Vichyssoise, a soup with pureed carrots instead of leeks and potatoes. The aesthetics of dining were also emphasized with attention to plating and a choice of dinnerware including colored glass, Delft, and Wedgewood for special parties. Prices were moderate and no alcoholic drinks were served throughout the 26 years of Mary Love’s control. During the 1940s a lunch could be had for 75 cents, just 15 cents more than the State Palace had advertised in 1919.

The story of Mary Love’s career in the restaurant business is intertwined with the rise of home economics programs in colleges and universities and with a growing attraction of women to the restaurant field. Women gained a new-born confidence that they could not only succeed in the restaurant and catering business, but do a better job of it than many of the men who had dominated it for so long.

Somehow Love raised considerable capital – $110,000 (at least 1 million dollars today) – when she incorporated the Mary Love Company in 1920. The officers of the company consisted of two male lawyers and two women, one a stenographer and the other co-manager of the restaurant. Her source of funding is unknown though it’s possible some of the officers also may have been investors. Certainly the common observation that women-owned restaurants of the 1920s were usually woefully undercapitalized did not apply in this case.

With ample financial backing Love was able to take over the entire building at 112 E. Broad Street. The ground floor held the main dining area and kitchen, the second floor was used for parties, and the third floor for baking. A confectionery and bakery shop occupied the basement.

Throughout her career Love relied upon a network of women, without whom it’s likely she would not have succeeded. In decorating the restaurant she turned to a Columbus friend who was a prominent impressionist painter and flamboyant colorist, Alice Schille. Schille had studied in New York with William Merritt Chase, and lived in Paris for several years.

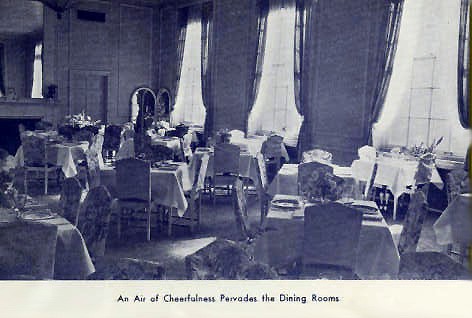

Schille designed jade green batik hangings with flamingos whose colors carried over to chair cushions and slipcovers. To create a sense of privacy for groups on the second floor she decorated screens color-coordinated with the room’s red-orange table tops. A visitor in the restaurant’s first year of business reported, “There are two floors, about two hundred seats, and the rooms are most pleasingly decorated.”

In 1927 the restaurant moved to 137 E. Broad, to a new building constructed for the restaurant, but large enough to accommodate additional retailers as well. As can be seen from images in a WWII-era promotional booklet for The Maramor, the restaurant had by then assumed a somewhat more stately appearance similar to an upper-middle class home of that time.

Mary Love had come a long way when she launched her restaurant. Born in 1890, she spent her early years in the small town of Horton, Kansas, in a family that broke up when she was 12 years old, sending her and her younger brother to live with relatives. After high school she taught for several years before putting herself through the home economics program at Kansas State Agricultural College in Manhattan.

Despite the difficulties she experienced in her young life she was popular and had many friends. While she was in high school they formed a cooking club, taking turns preparing dinner together at each other’s houses twice a month. Love considered this a formative experience, stating in a 1915 interview, “We learned to cook, which is just as much an art as drawing a picture or playing a sonata.” As unexceptional as that sentiment might sound today, it was novel then. Few women of that time would have regarded cooking as a fine art. Rather they viewed it as drudgery best left to a servant.

The low status of cooking in the early 1900s, the disdain for it among middle-class women, was one of the problems home economics programs were meant to address – along with preparing some students for institutional food service careers. A bit later the restaurant industry began to organize locally and nationally to improve eating places. In mid-1920s Myron Green, president of the National Restaurant Association, told a conference of home economists that his organization had been founded to uplift an industry that had long been “second rate.” He also said, “The greatest need of the restaurant and hotel industries of today is the refining and cleansing influence of woman.” Progressive restaurant owners and managers then were aware that growing numbers of the middle class were patronizing restaurants and that they expected cleanliness, high quality food, and attractive surroundings — all qualities that were rare in the average restaurant.

It was just this clientele that Mary Love had served in her previous jobs running department store tea rooms. Known for her organizational skill, she had been recruited while still a student at Kansas State by the Rorabaugh-Wiley dry goods store in Hutchinson KS to install a tea room in the store’s new building. After one year on the job Simon Lazarus, executive of a bigger store in a bigger city, the F & R Lazarus department store in Columbus OH, offered her a high-salaried job running a bigger tea room. In addition to the store’s tea room, she was also in charge of the men’s café and the employee cafeteria. By 1917 she reportedly made $4,000 a year, more than the average chef in New York City.

In her years at Lazarus, Mary Love assembled teams of managers much like she would do when she established The Maramor, using her network of Kansas friends, Kansas State classmates, and members of the Pi Beta Phi sorority in both Kansas and Columbus. She was also a founding member and officer of Columbus’s Altrusa Club of business and professional women formed in 1918.

Mary Love’s team approach was critical to The Maramor’s survival after she married a California man, Malcolm McGuckin, and moved to Pasadena in 1921. With her trusted women employees in charge, her restaurant prospered and prepared to move to its new location. Remarkably, Mary was able to stay involved with the restaurant from afar over a period of five years in which she had three children, traveling back to Columbus twice a year by train.

After the failure of the automobile manufacturer her husband worked for in 1927, the McGuckin family moved back to Columbus and resumed direct management of the business. Malcolm replaced Mary as president of the company, but women continued in all the management positions until after WWII when three male veterans were appointed as general manager, night manager, and candy production manager.

The Maramor’s guest book contained glowing comments from local patrons and visitors from far and wide, some of them stage personages appearing in Columbus. Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas almost certainly ate there during a 1934 visit to Columbus. As a friend of Alice Schille, it seems very likely that Toklas was referring to The Maramor when she later wrote: “In Columbus, Ohio, there was a small restaurant that served meals that would have been my pride if they had come to our table from our kitchen. The cooks were women and the owner was a woman and it was managed by women. The cooking was beyond compare, neither fluffy nor emasculated, as women’s cooking can be, but succulent and savoury.”

In 1941 Mary Love McGuckin reported at a home economics conference on how her restaurant kitchen was organized. She avoided frying and prepared fresh vegetables carefully to retain their flavor and vitamins. Food was cooked in small batches so that it would not lose freshness before being served. Each day her planning department presented the production manager with the day’s menus, while a weighing and measuring specialist prepared trays with complete ingredients for every dish. The trays were given to the cooks, along with detailed instructions for cooking. “This,” Mary said, “helps them to keep their poise and self-respect through the working day, and a cook with poise and self-respect has a better chance of turning out a good product.”

Mary’s business career was terminated due to Malcolm’s deteriorating health. In 1946 the couple sold The Maramor and returned to California. That same year Mary’s collaborative management style was featured in a Journal of Home Economics article by organizational sociologist William Foote Whyte. Whyte characterized it as an “open-minded exploratory approach” that stressed listening, participation, and sensitivity to others’ feelings. Mary recommended that managers keep notes from staff meetings and follow up later to see if issues had been resolved.

The Maramor continued in business under its new owner, Maurice Sher, into the 1960s. Even today it is remembered as one of the city’s hallmark restaurants.

Jan Whitaker is the author of Tea at the Blue Lantern Inn: A Social History of the Tea Room Craze in America and of the blog

Jan Whitaker is the author of Tea at the Blue Lantern Inn: A Social History of the Tea Room Craze in America and of the blog